Versión en español

His latest visits have made him sad

Deciderio Cepeda got his respect for nature from the Warao Indigenous people, to which he belongs, just as he got his woodworking skills from his father. At the age of twelve, he decided to put both to the service of his community, until he could not anymore because of the surrounding context. Yet, he does not lose hope that one day he will be able to do it again.

There were no Warao here in the beginning.

No Warao had been born to our entire land.

All the Warao, our ancestors, were right there, up above.

Our Grandpa was right there, up above.

So, the Warao lived right there, up above. There were no Warao here.

Manifestaciones religiosas de los waraos, Antonio Vaquero.

“Brother Tree, I come to ask your permission.”

Deciderio Cepeda performs the ritual exactly as his father —who was also a woodworker and a dugout maker—, taught him when he was twelve: first, he talks to the tree; only then can he proceed to cut the wood he needs to repair the stilt houses they call palafitos.

Over the years, he and his brothers mastered the craft and started using chainsaws. By the time he was 18, they all knew how to make wooden boards, which they used to replace the houses’ palm walls. One day, a neighbor of theirs approached them: “I would also like to have a house like this made for me.” And they helped him. Shortly after that, another neighbor came with a similar request, and then many others. If they could afford to pay them something for their work, fine, but if not, they would fix their stilt houses anyway because, in the end, that is what the Warao do: they support each other’s families.

“The Warao need to know how to build their own houses,” adds Deciderio, now a grown man.

Palafitos are gable roof houses built to stand above the river’s water. They are covered with leaves of temiche palm trees, and their manaca wood floors are always above the highest tide.

But in the middle delta, where Deciderio lived, houses were made differently because the tide there is dry for six months or so every year. Deciderio’s house was made of interwoven sticks and mud, or bahareque, as it was on dry land.

Now, at the start of the rainy season, when the tides were high, they would drive sticks into the ground to hang their hammocks, sort of a stilt house inside their house, or a bunk bed, where they lived safely during the high-tide months. And when the water level receded at the start of the low-tide season, they would take the structure down and repair the wall segments that had been under water for months.

Every six months, every year, for years and years.

Until he got married.

His wife lived in Nabasanuka, in the lower delta, and he had to travel from his caño to hers, but he moved in with her eventually. Since high and low tides in the lower delta occur twelve hours apart, the palafitos, which are built on manaca poles, are always above the highest tidal level and need frequent repair. He had more to do in Nabasanuka.

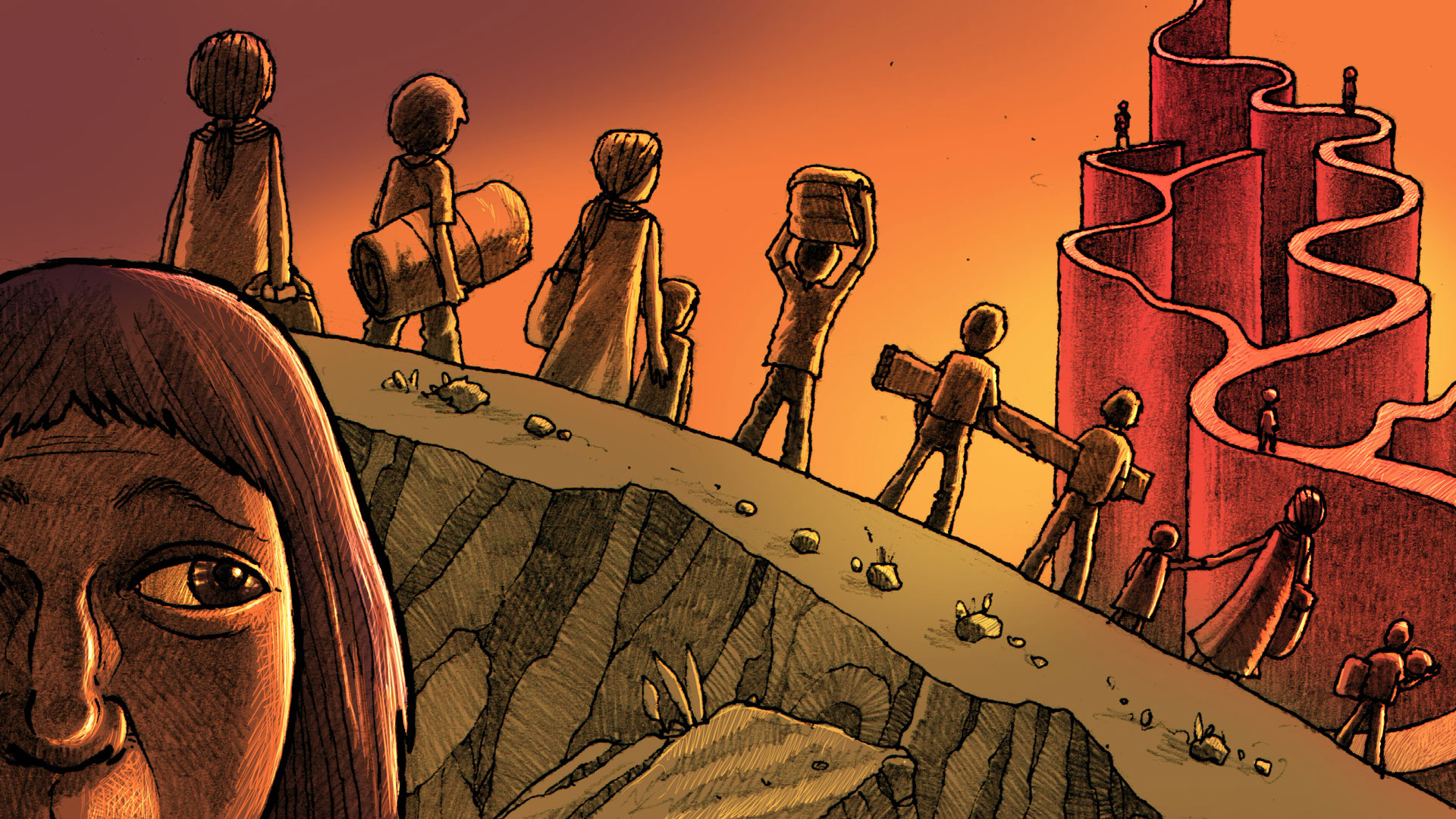

Soon, his work in other communities would allow him to provide for his family, and he single-handedly improved the quality of life of his people and gave others a possibility to stay, because many began to leave.